|

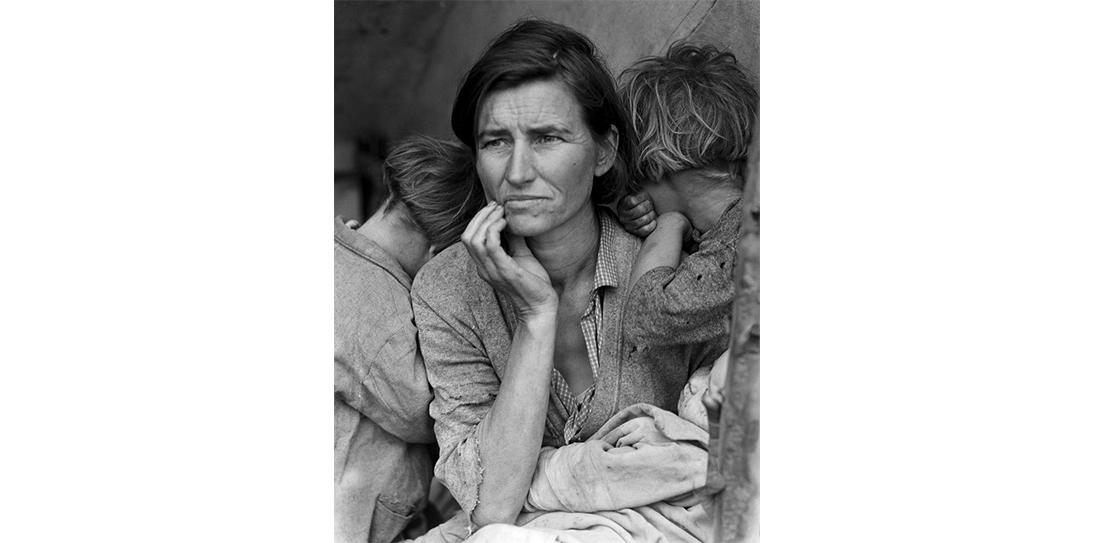

Migrant Mother: Florence Owens Thompson and her children, pea pickers’ camp, California (Barbican.org.uk) ‘A double bill of exhibitions featuring pioneering documentary photographer and visual activist, Dorothea Lange, and award-winning contemporary photographer, Vanessa Kinship.’

‘Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing retrospective of American photographer Dorothea Lange (1895-1965). Barbican Art Gallery, 22nd June to 2nd September 2018 The first room mildly irritated me - beautiful photographs taken in Dorothea Lange's San Francisco studio, often of her pals. I’m tired of wealth and contacts determining what culture is and giving the well positioned a place in history. The second room shared Lange's wake up call, with street photography during the Great Depression which was followed by more and more and more rooms and rooms of committed photography mainly depicting economic refugees. Portraits that were so personal, close and natural it was hard to imagine how they could have been taken on her camera of the day. Lange's most famous image of a woman living in a tent with her children at the roadside 'Migrant Mother', was exhibited in a small room with a series of this family. Lange was quoted as saying it was a collaboration that felt quite equal, for the woman seemed to know the images would help her. This seemed a bit much, standing in the Barbican galleries in a solo show of this photographer’s work across years, countries, continents… my friend remarked it was unlikely she’d stayed in the tent, when I mentioned my gripe. It got me thinking about the often difficult relationship between the subjects’ of journalism and a journalist's output. There are of course many in the field of foreign correspondence who help raise awareness and give everything to bring truth to the surface; though sadly it can appear they are the minority. Many visible in the industry have been known to work with people who are already suffering and 'done to', then produce images and stories that have a different slant or purpose to that which was alluded to in forming the alliance. Further to this, ethics regarding the methods used can be questionable. Disclosing stories of suffering can be re-traumatising even in the most private and safe of environments, but often civilians still living in traumatic and unsafe circumstances tell their stories without any safeguarding or support system in place. In the case of the Yazidi women and girls in recent years it seemed there was as much voyeurism at play as attempts to help them - with unnecessarily detailed reports of rape and sexual slavery; the subjects of these stories even being further endangered by their anonymity not being sufficiently protected. That hard to tread line between exploitative and responsible journalism, is also slimmed right down by opportunity - by what people choose to read. The information in this exhibition included who was commissioning Lange on her photography assignments, there were a few mentioned, though The Farm Security Administration seemed primary. This was helpful to know, though her incredible focus and consistency in style and content did have a more self-initiated feel to it - a labour of love. I guessed that she already had her basic needs met and the commissions embellished this rather than sustained her. It’s notable she is described here as a founder of documentary photography rather than an early photojournalist. One room fairly mid-way in housed powerful and moving documentation of the Japanese Americans being deported after the attack on Pearl Harbour - enabled by an assignment from the War Relocation Authority to document the relocation (or incarceration) of the Japanese diaspora. Lange was against the treatment of these communities and used her photography as a critical tool: as this was not what she was asked to do the work remained largely unseen. It was so sad to view the faces of children with parcel labels hanging around their necks, who might not even speak any Japanese. Apparently many pictures were missing where she had photographed the deportees draped in stripes of light that made them appear as though they were in prison. My friend pondered the scale of World War II - this huge expulsion of American citizens with Japanese descent being a little known part of it. I found it impossible to ignore how easily people can be pitted against each other, when with limited resources and political provocation or propaganda. The show ended on a softer note in Ireland, which seemed to interest her less. It really was the Dust Bowl images that stuck with me - and the Japanese children pledging allegiance to the American flag, wondering what on earth was going on and having to just go. Vanessa Kinship didn’t do too well being upstairs from this show. The strength, consistency and depth of Langes collection shining even brighter and making Kinship seem quite whimsical, with curation that didn’t so much nod toward high end art but rather screamed and pointed. Minimal labels on Lange's work told you who, where and what. The presentation of Kinship's photography asserted the viewers take what they will from the no label images, which felt a bit easy for both artist and viewer. There was an interesting room of portraits from Georgia, which would stand alone well; though they felt like a flicker of light after the roaring fire below. I could probably do with seeing the Kinship show on a different day. Actually I definitely could, aiming to enjoy the diversity of her practice and resist the urge to be disparaging of it. It's too easy to dismiss contemporary practitioners... though equally important not to be overly influenced by framing. The Dorothea Lange collection of images were all (as far as I remember) silver gelatin prints and this could be a camera she used (for Migrant Mother): Graflex Super D - lommen9.home.xs4all.nl/Graflex%20Series%20D/ The Barbican's say: barbican.org.uk/our-story/press-room/dorothea-lange-politics-of-seeing Comments are closed.

|

Lee's memoirsReviews of shows / events log and share experiential references. Archives

June 2024

|